Mountains and Waters: Reading Chinese Landscape Paintings

Beyond mere scenic views, Chinese landscape painting unveils a philosophical dialogue between mountains and waters. Discover how ancient masters used simple black ink to capture nature's profound essence, creating worlds where every stroke tells a story of harmony and contemplation.

My first encounter with a Northern Song landscape scroll came on a quiet afternoon in Beijing's Palace Museum. The painting, nearly a millennium old, hung before me like a window into another world - not merely a view of mountains and waters, but a complete philosophical statement rendered in ink.

The Chinese term shānshuǐ(山水) tells us much about this art form's essence. These paintings are not simple scenic views, but careful studies of the relationship between the eternal mountains and the flowing waters. Before the Tang Dynasty (618-907), artists began developing this visual language, which would reach its full maturity in the Song period (960-1279).

,%20Stroll%20About%20in%20Spring%20The%20Palace%20Museum%20%E6%94%B6%E8%97%8F.jpg?updatedAt=1736047581107) Fig.1 Zhan Ziqian (Sui Dynasty), "Stroll About in Spring," Collection of The Palace Museum

Fig.1 Zhan Ziqian (Sui Dynasty), "Stroll About in Spring," Collection of The Palace Museum

The viewing of these paintings follows specific principles. Unlike Western landscapes that present a fixed viewpoint, Chinese paintings invite a journey through the composition. A small figure - perhaps a sage or traveler - often appears at the bottom, providing both scale and an entry point. From there, the eye travels upward through carefully structured spaces.

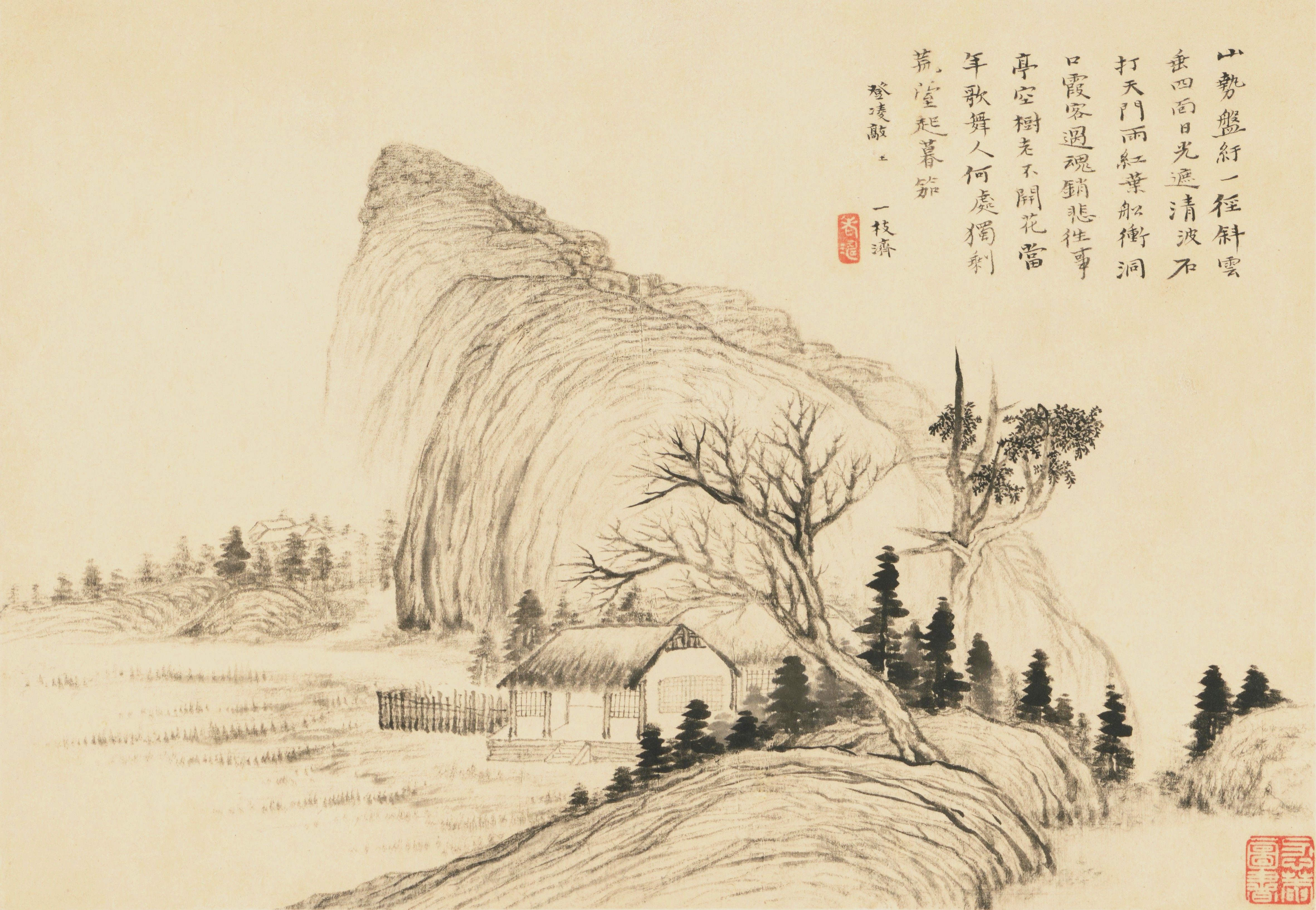

The mastery lies in the brushwork. Using only black ink in five gradations, from deep black to the palest gray, artists create an entire world of form and texture. Mountains emerge through careful layering of strokes, while waters take shape through subtle tonal variations. The apparent simplicity of materials belies the complexity of technique.

Fig.2 Ma Yuan (1160-1225), "Viewing the Moon," Fan painting, Collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig.2 Ma Yuan (1160-1225), "Viewing the Moon," Fan painting, Collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Space in these paintings is organized through three classical distances:

- High distance (gaoyuan), where peaks rise above clouds

- Deep distance (shenyuan), revealing layers of landscape

- Level distance (pingyuan), stretching across open spaces

The white spaces serve a crucial role. What might appear as empty paper actually represents mist, clouds, or atmosphere. This interplay between the painted and unpainted areas creates depth and suggests the dynamic forces of nature. The void, in Chinese painting, is never truly empty.

Fig.3 Shitao (d.1707), "A Leaf from Landscape Album," Collection of The Palace Museum

Fig.3 Shitao (d.1707), "A Leaf from Landscape Album," Collection of The Palace Museum

Natural elements carry specific meanings while serving compositional purposes. Pines speak of endurance, bamboo of resilience, and flowing waters of constant change. Yet these symbolic readings never overshadow the artistic unity of the whole. Each element contributes to a larger visual harmony.

For the Western viewer, understanding these paintings requires patience and a willingness to set aside familiar artistic conventions. The multiple perspectives, the role of empty space, and the use of ink rather than color all follow different principles than European tradition. Yet these differences offer fresh insights into how art can capture the essence of the natural world.

,%20Landscape,%202018%20.jpg?updatedAt=1736047581254) Fig.4 Mo Lijia (b.1986), "Landscape," 2018

Fig.4 Mo Lijia (b.1986), "Landscape," 2018

Today's artists continue to draw inspiration from this tradition, finding in its principles answers to contemporary questions about human relationships with nature. These ancient works, with their careful balance of technique and philosophy, remain remarkably relevant to modern viewers.

In the end, Chinese landscape painting teaches us that seeing nature means more than recording its outward appearance. It requires understanding the underlying patterns and relationships that give the natural world its character. This lesson, first developed by Tang and Song masters, continues to resonate across centuries and cultures.

Fig.5 Wang Yi, "Page One of the Landscape Album," 2023

Fig.5 Wang Yi, "Page One of the Landscape Album," 2023